Alone together? How social technology is influencing human connection and loneliness

We examine loneliness and social connectedness of users on different social media platforms, as well as beliefs about how social media affects connection.

How people connect and bond with each other is constantly evolving. Perhaps the most important shift in the modern age is the movement away from organized in-person communal activities and toward more online social activities. Over the past several decades, this shift has drastically changed the structure of social interaction–with potentially drastic consequences–in at least four ways we outline below.

How is social technology changing humans’ social lives? Four big changes.

First, much of conversation has become text-based (e.g., online chatting, texting, direct-messaging); more than half of young people’s social interactions now occur via text. Unfortunately, the written medium, while sometimes appealing in its clarity and precision, tends to be a uniquely dehumanizing form of communication: facilitating anonymity, heightening disagreement, poorly conveying communicators’ mental capacities (e.g., thoughtfulness, emotionality), and reducing empathic accuracy.

Second, online tools can create barriers to productive and enjoyable in-person interaction. Merely having a phone (or other screen) in hand during a live interaction undermines the enjoyment of that interaction and social connection more broadly, makes parents feel more distracted and disconnected, and generally can lead people to substitute engagement in the offline world with engagement in the online world.

A third major change has been the emergence of generative pre-trained text tools based on large language models (LLMs) in online spaces that can interact convincingly and synchronously with humans (e.g., chatbots). Most people now have been faced with the confusion of interacting with an online agent and not knowing whether or not it is human (the real-world instantiation of the famous theoretical Turing Test), and some have even insisted that known bots are sentient. Such ambiguity in the identity of one’s online interaction partners may be contributing more broadly to a sense of dehumanization in social life, leading to new investigations into how to signal humanness in online spaces.

Of course, perhaps most pertinent of all has been the advent of social media, which many have argued has facilitated echo chambers, filter bubbles, misinformation, and polarization at large scale. Yet the consequences of social media for social connectedness are potentially mixed. Potential benefits include more explicitly defined and easier to use networks, and larger audiences for everyday people to easily access (“influencers”). Regarding the relationship between loneliness and social media, whereas some studies suggest that social media “overuse” corresponds with greater loneliness, other studies instead find that social media can help people connect with others. The relationship may be complex; it could be that whether using social media is helpful or harmful depends on the motives of its users, or the way in which social media is used (e.g., passively or actively).

Indeed, it is important to note that not all technological advancements in social life have necessarily reduced the quality (or quantity) of social connection. Online communication platforms allow us to transverse enormous geographic distances in mere seconds, give us the ability to communicate with loved ones during pandemics, provide communities for those of us who previously might have had challenges finding them (e.g., video gamers), and create opportunities for efficient social matching (e.g., dating or friendship match websites).

Aggregating across the aforementioned changes, what are the net consequences for social life in an increasingly online world?

One of us (Schroeder) has proposed that humans are becoming “undersocial” - less social than they could be to maximize their own and others’ well-being. Whereas technology may be facilitating undersociality, Schroeder argues a more primary factor is people’s broken mental models regarding social connection. For example, people tend to overestimate the riskiness of social interaction, which can lead them to avoid novel social experiences (e.g., interacting with strangers) or, when they do engage, to do so in less intimate ways (e.g., preferring texting to speaking). Indeed, evidence is accumulating that people make maladaptive social decisions across a wide range of situations, from choosing to interact via writing even though speech is more humanizing, to avoiding interaction even when it would be pleasant, to ending a conversation even when talking longer would have been enjoyable, to choosing to discuss shallow topics even though more is gleaned from deeper topics.

Understanding the phenomenon of undersociality, and the role of technology in facilitating it, is important because politicians have declared that a loneliness epidemic is sweeping our nation. Loneliness accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic; some argue that loneliness persists post-pandemic – an argument we will address later in this post. Loneliness has severe negative consequences for people’s mental health (social connection is a fundamental human need), and physical health (e.g., elevated risk for cardiovascular disease, cognitive impairment, depression, diabetes, societal polarization, and even premature death).

Schroeder’s TEDx talk describes why people are undersocial, how it contributes to the loneliness epidemic, and suggests ways to connect better. Redesigning our social worlds to facilitate connection instead of disconnection may require not just overhauling social technology but also rewiring our psychology toward a more generous, other-oriented mindset – an idea that TED’s Chris Anderson is calling “infectious generosity” and the need for which we empirically document (we argue that kindness is chronically in short supply).

So how concerned should we be?

We see the following reasons for concern: 1) social technology is, at best, under-delivering on its promise to improve human connection, 2) loneliness has dire negative consequences for mental and physical health, and 3) people’s psychology in the changing social world appears poorly equipped to optimize their health. But as scientists, we also note that low-quality data has made it difficult to draw conclusions regarding the true relationship between social tech, loneliness, and connection. Indeed, there is much debate about whether loneliness really has been meaningfully increasing over the last several decades and whether social media, on the net, has helped or harmed our social lives.

In the rest of today’s post, we try to shed light on what we believe is a complex relationship between social media use, loneliness and connection, and people’s beliefs about social media’s association with loneliness and connection. To do so, we use a novel data source that other scholars have not yet analyzed for this purpose: the Neely Center Social Media Index (SMI) survey. Given that the SMI is descriptive and not experimental, we cannot make any strong claims about whether social media is causing more or less loneliness. Instead, we describe differences in loneliness among subpopulations and across platforms, and theorize why those differences may exist.

Measuring Loneliness and Social Media Beliefs

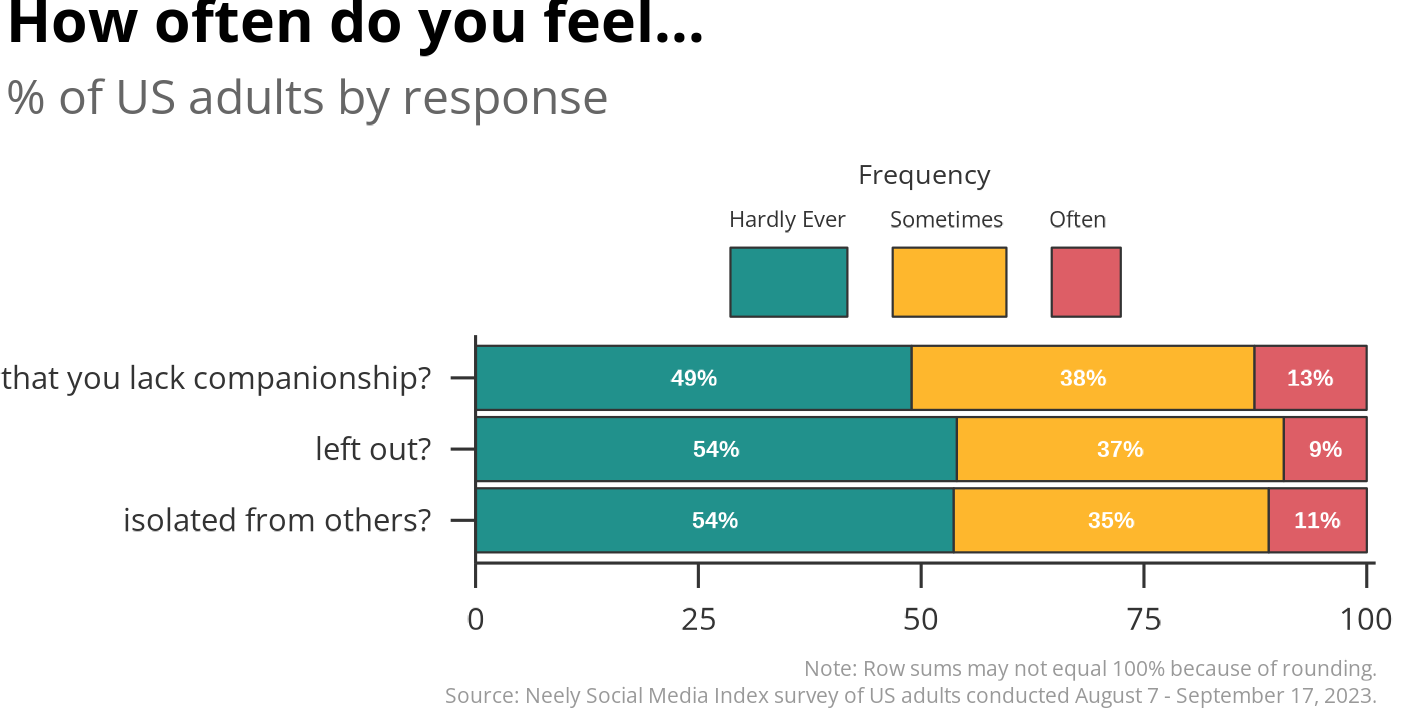

Before looking at how loneliness may vary across platforms, or for people with different beliefs about social media, let’s review how we measure these two concepts. One of the most widely used surveys assessing loneliness is the UCLA Loneliness Scale. This survey was designed to measure people’s subjective feelings of loneliness and social isolation by asking people how often they have certain feelings about their connections with others. Researchers have developed a shortened 3-item version of that questionnaire for use in contexts where time is limited.

Those 3 questions may be seen in the graph below. Specifically, respondents were asked how often they felt each of the experiences labeled on the y-axis. Across each question, a plurality, if not a majority, of US adults reported that they felt those loneliness-related experiences “hardly ever.”

Then, responses for these three questions are combined to generate an overall loneliness score ranging from 3 (where a respondent chose “Hardly Ever” for each of the experiences) to 9 (where a respondent chose “Often” for each of the experiences). Based on past research, respondents are deemed lonely if they have a score of 6 or greater. The histogram below shows the distribution of these summary loneliness scores. About 36% of US adults meet the criteria for being lonely. This number exceeds the 21-25% estimate from Gallup in 2023, matches what another nationally representative survey found in 2021 (but note that those data employed a stricter criterion for measuring loneliness), and is below the 46% estimate found in another 2023 survey that used the same questionnaire. Given standard measurement error and constantly changing societal events, our estimate is reasonably consistent with similar polls being conducted.

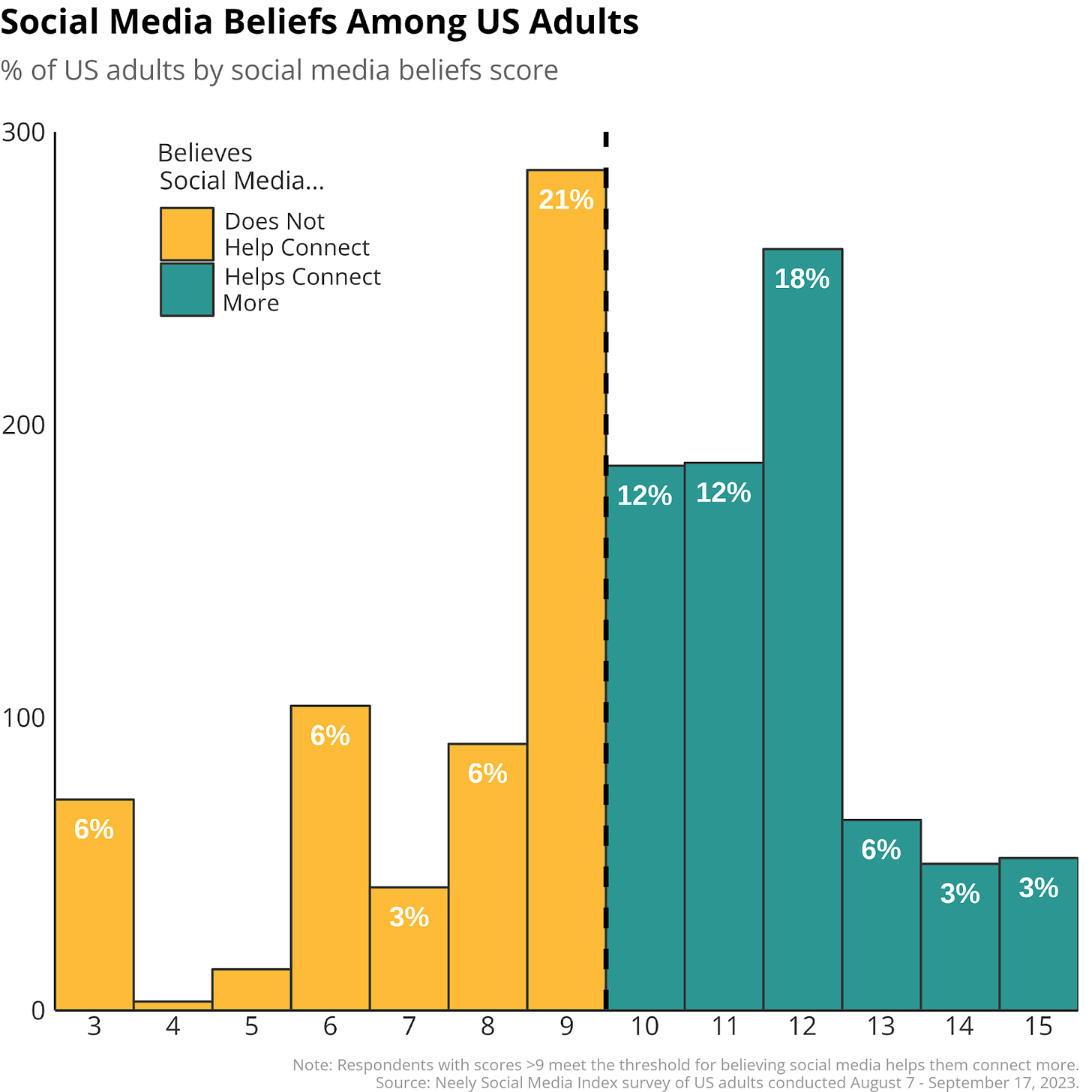

Given that some past research suggests that people’s beliefs about social media use might affect whether social media helps them to connect with others and stave off loneliness, we also included another questionnaire designed to capture these beliefs. This questionnaire also includes 3 questions that ask respondents to indicate the extent to which they agree or disagree that social media helps them connect more with friends, families, and neighbors and others. As seen in the pyramid plot below, a majority or near-majority of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that social media helps them to connect more with friends and family. Yet fewer agreed with respect to others (e.g., neighbors). These numbers are nearly identical to those reported in another survey of US adults in 2023.

Much like the loneliness scale, I (Motyl) combined responses across these three questions to create a summary score for use in later analyses. Specifically, if people agreed more than they disagreed, or neither agreed nor disagreed, they were classified as believing that social media helps them connect more with people. Otherwise, they were classified as not believing that social media helps them connect more with people. The raw distribution of these scores is shown in the histogram below with the dotted vertical line indicating the cut-off for beliefs about social media’s connective power. By our cut-off, just over 54% of US adults believe that social media helps them connect more with others.

Loneliness and beliefs about technology have varied among people with different demographic and social identities in past research. To examine this in the latest data, Motyl created the table below showing the weighted percentage of US adults who are lonely and the weighted percentage of people who believe that social media helps them connect more with people broken out by people’s group identities. Several interesting findings emerge. Women are lonelier than men, but are more likely to believe that social media helps them connect. Younger people are lonelier than older people (an interesting result in itself, and consistent with several other research results), but social media beliefs are rather consistent across age groups. Less educated people are lonelier than more educated people, but seem not to differ in their social media beliefs in a clear, consistent way. Republicans and those who lean towards the Republican Party tend to be less lonely and more likely to believe that social media helps them connect than are Democrats, those who lean towards the Democratic Party, and political Independents. Black, non-Hispanic and Multiracial, non-Hispanic people are lonelier and less likely to believe that social media helps them connect with others than are White and Asian, non-Hispanic people. Lower income people are also lonelier and less optimistic that social media can help them connect to others than higher income people are.

If loneliness stems from lack of social connection and people believe that social media helps them connect with others better, then using more social media should correlate with less loneliness. This is not the case. There is a small, but statistically significant positive correlation (⍴(1413) = +.09, q < .001) between loneliness and the number of different online platforms (e.g., social media) someone uses. Additionally, there is a positive correlation (⍴(1413) = +.12, q < .001) between people’s belief that social media helps connect more to others and the number of different platforms used. In other words, lonelier people and people who believe social media helps them connect more with other people use a greater number of social media platforms than less lonely people and people who do not believe social media helps them connect more with others. It makes sense that if people believe social media helps them connect with others more they will use social media more. In light of this belief, though, it is somewhat paradoxical that the more social media platforms someone uses the lonelier they are.

There are several possible explanations that could resolve this seeming paradox. For one, perhaps lonelier people flock to social media and other online platforms as a (potentially misguided) means of alleviating their loneliness. For another, it could be that the raw total number of different social media platforms used is too crude of a measure to assess social media use. Fortunately, our respondents also indicated how frequently they used each social platform in the last 28 days, ranging from less than once per week to multiple times per day. In the table below, Motyl reports the correlation between respondent-level loneliness and their frequency of using different social platforms.

Generally, frequency of use does not seem to correlate with an individual’s loneliness. The exceptions to this are YouTube, Facetime, and Text Messaging. The more frequently people reported using YouTube and Facetime, the less lonely they tended to be. In contrast, the more frequently people reported Text Messaging, the more lonely they tended to be. Overall, correlations were statistically non-significant on 13 of 16 social platforms, and only quite small on the remaining 3 platforms.

Given these data patterns, we think at least three possibilities exist:

There is very little to no relationship between social media use and loneliness,

Self-reported measures of social media use are biased and obscure a relationship that might emerge if looking at the actual behavioral data of using platforms, or

The relationship between the frequency of using social media and loneliness is more nuanced than can be observed in a simple correlation.

As discussed in more detail later, we are partial to possibility #3.

In the next section, we dig deeper into how people who use different platforms have different beliefs about social media’s connective power, and how experiences on social platforms may relate to higher or lower levels of loneliness.

Loneliness Across Social Media

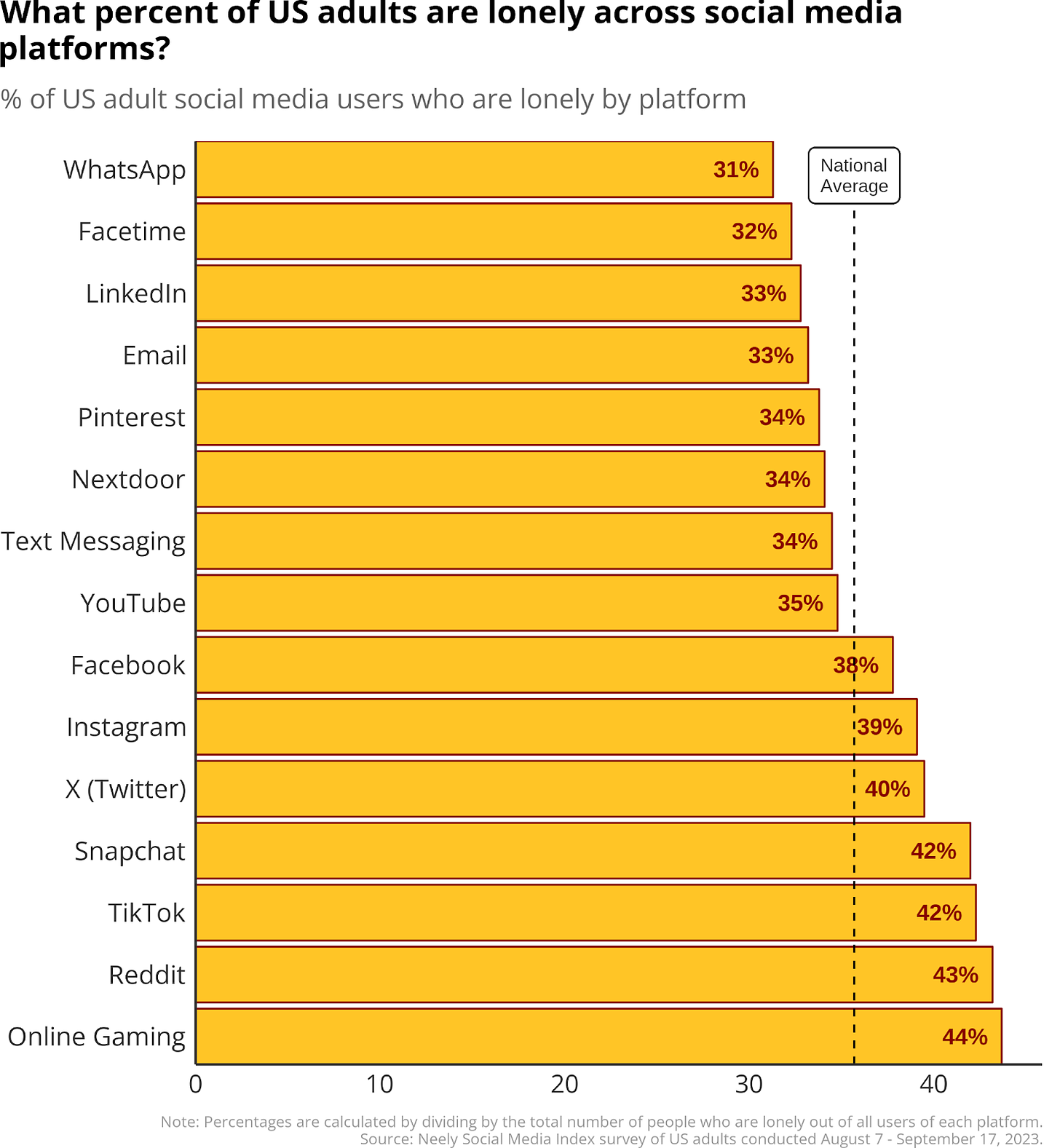

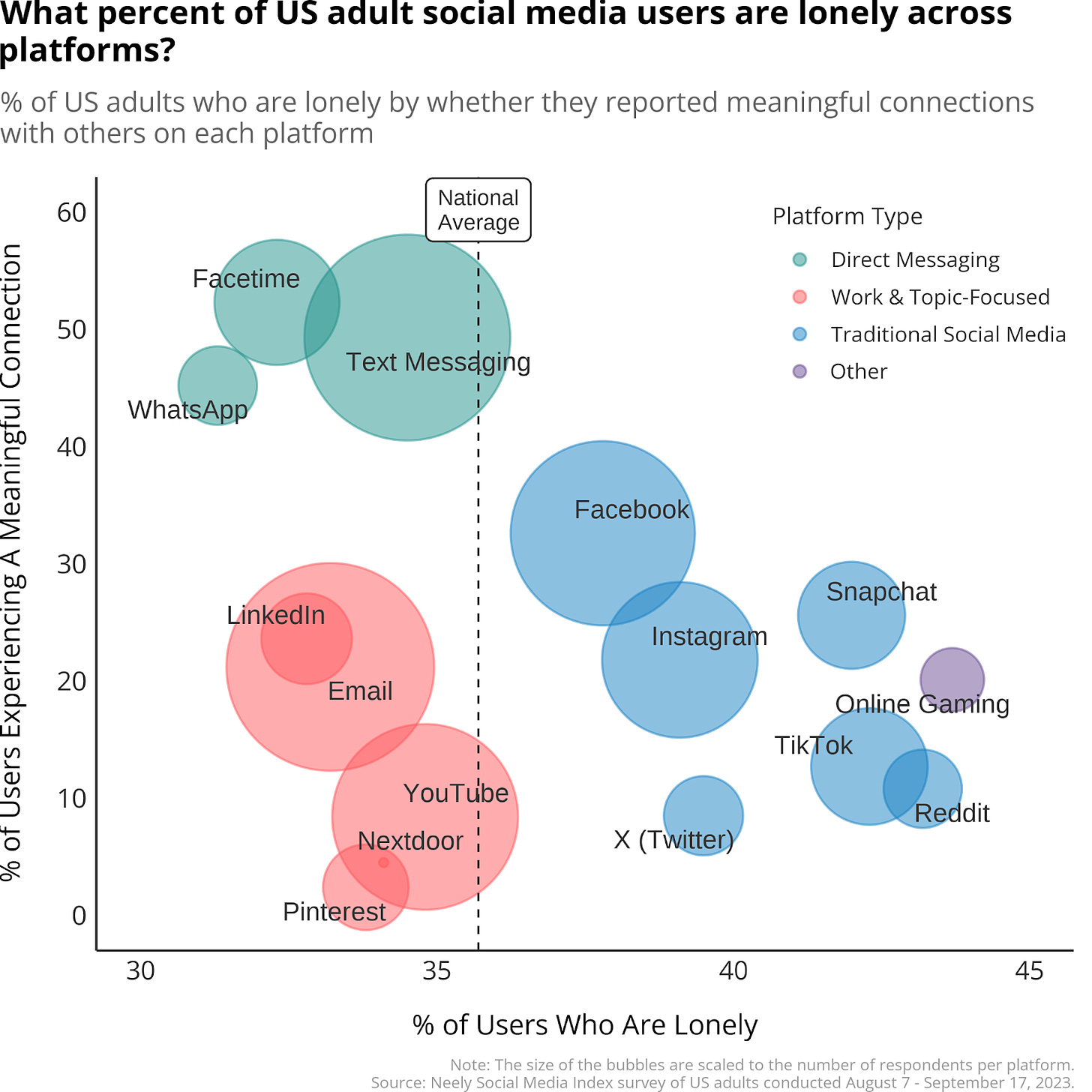

Different social platforms serve different purposes and may appeal to people at different times depending on how they are feeling and what they are seeking. Our past analyses demonstrate considerable variability in the rates at which people have negative experiences, learn new and important things, and form meaningful connections with others across platforms. Therefore, we’ll start by looking at the percent of users on each platform who are lonely and see how the platforms compare to each other and to the national average.

In the bar chart below, the national average of loneliness is 37% and represented by the vertical dotted line. The average user of WhatsApp, Facetime, LinkedIn, and Email was slightly less lonely than the national average, and significantly less lonely than the average user of Online Gaming, Reddit, TikTok, Snapchat, and X (Twitter). 3 of the 4 platforms with the lowest average percentage of lonely users were all direct messaging tools, which also matches our earlier finding from a previous wave of this survey where direct messaging platforms tended to facilitate meaningful connections between people at a higher rate than other types of social platforms.

In the current wave of our survey, we also find that these direct messaging social platforms continue to have the highest rates of people reporting meaningful connections with other people. Notably, the rate of people experiencing meaningful connections with others via the asynchronous and text-based platform of email is significantly less than the synchronous platforms of Facetime, Text Messaging, and WhatsApp. For platforms where users likely do not seek out social connections, like Pinterest, we see that despite those users not reporting meaningful connections with others on that platform, they also are not particularly lonely. Thus, this may support the hypothesis that people have different expectations of the platforms, and may be affected differently based on whether their expectations, motivations, and experiences align, or it simply may reflect differences in the types of people who tend to use different platforms.

Might Making Meaningful Connections with Others on Platforms Reduce Loneliness?

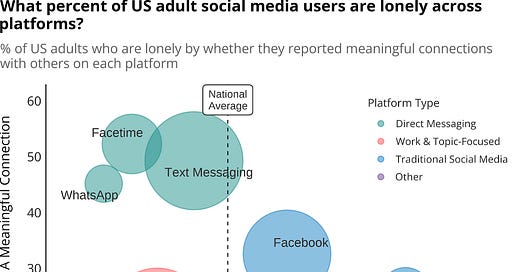

If we look at the platform-level relationship between people reporting a recent meaningful connection with other people on that platform and user loneliness, we see a moderate-sized but non-significant negative correlation (⍴(15) = -.32, q = .25). Given the small number of large social platforms, it is unlikely that the correlation would be statistically significant due to the error terms in the statistical formula. Yet, as can be seen in the bubble plot below, platforms with users reporting the highest rates of meaningful connections with others also tend to have the lowest percentages of lonely users. Thus, this is consistent with the idea that lonelier people are using less connective social technology.

There are also three main clusters of platforms in the bubble plot. First, we see the direct messaging platforms (the green bubbles), which have high rates of meaningful connections between users and low rates of loneliness. Second, we see the work-oriented (e.g., LinkedIn) and topic-focused (e.g., Pinterest, YouTube) platforms (the red bubbles) tend to have low rates of meaningful connections between users and low rates of loneliness. Lastly, we see the more traditional social media platforms (e.g., Facebook, Snapchat; the blue bubbles) tend to have lower rates of meaningful connections between users and higher rates of loneliness. The fact that these social connection-focused platforms tend to have lower rates of meaningful connections between users and higher rates of loneliness suggests conflict with many of their mission statements. For example, Facebook and Instagram’s parent company’s mission statement has long been to “give people the power to build community and bring the world closer together.”

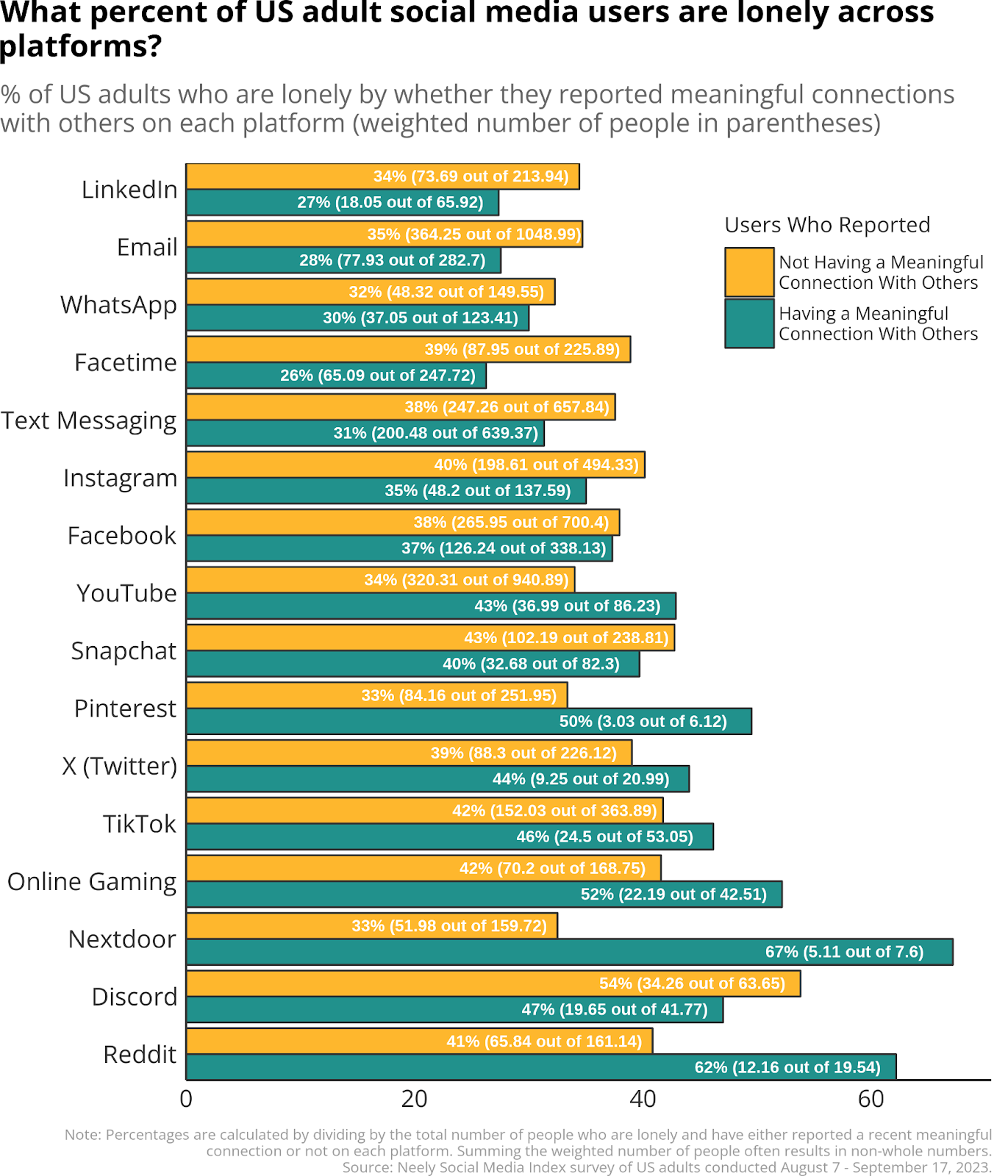

In the plot below, we compare the rates of loneliness among users who reported making a recent meaningful connection with others on each platform vs. who did not report making a recent meaningful connection with others on each platform (i.e., a within-platform analysis). For example, 34% of the ~214 people who reported using LinkedIn and not having a meaningful connection in the past 28 days also reported being lonely; in contrast, only 27% of the ~66 people who reported using LinkedIn and having a meaningful connection in the past 28 days also reported being lonely. (Note that the absolute number of people in each bar reflects the weighted average of the nationally representative sample, and that some bars have very few total people represented in them.) Overall, for larger platforms and most direct-messaging platforms, the users who reported having a meaningful connection tended to be less lonely than the users of those same platforms who did not report having a meaningful connection. For smaller platforms and those with low overall rates of users reporting meaningful connections with others the numerical pattern essentially flip-flops, but the margin of error for people reporting a meaningful connection on those platforms exceeds the difference between the groups suggesting that these differences are not statistically significant and may be unreliable.

It is possible that lonely people experience social platforms differently than non-lonely people. In the graph below, we see that lonely people are somewhat less likely to report experiencing a meaningful connection with others on all of the direct messaging platforms. The only platform where lonely people are significantly more likely to report meaningful connections with others than non-lonely people is Online Gaming. Otherwise, people who are not lonely report either higher rates of meaningful connections on platforms, or there is no statistical difference between lonely and non-lonely people in their rates of reporting meaningful connections.

Across each of the above analyses, loneliness and experiencing meaningful connections are generally negatively correlated with each other. It would make sense that experiencing meaningful connections decreases loneliness and seeking, but failing to find those meaningful connections increases loneliness. However, these data are correlational, so we cannot be sure of whether one of these things causes or has an effect on the other. To make that determination, we would need platform-level experiments where users were randomly assigned to have meaningful connections (or not), and then assess loneliness among the users in each of those experimental conditions.

Might Negative Experiences on Platforms Increase Loneliness?

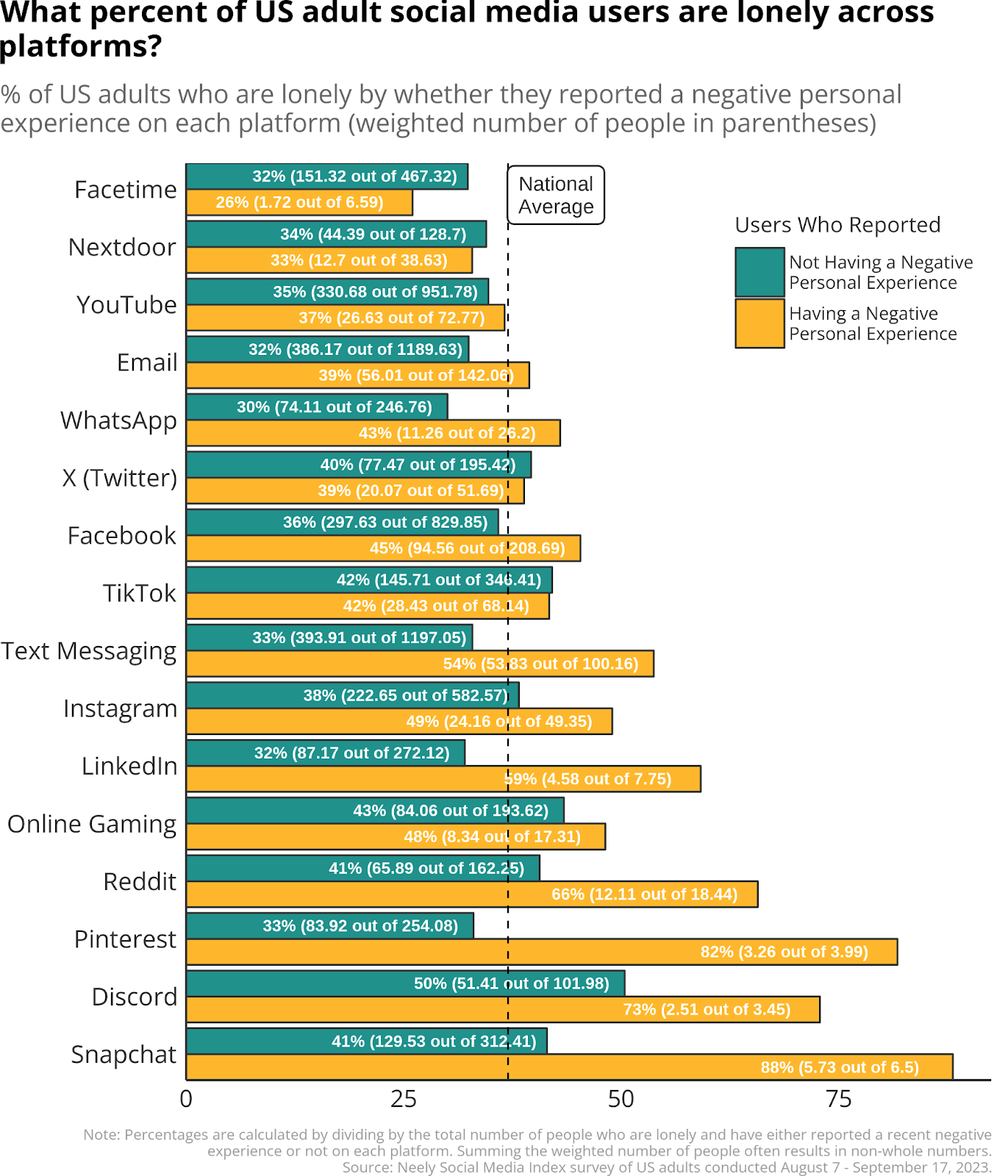

Our past research demonstrates considerable variability in negative experiences across platforms and satisfaction with one’s social life across platforms. US adults who reported negative experiences on these platforms often indicated that that experience worried them, made them lose trust in other people, and that it hurt their psychological well-being. Therefore, it is reasonable to predict that people who have negative experiences on social platforms might also be lonelier.

In the plot below, we see that for nearly every social platform people who had a negative personal experience were lonelier than people who did not have a negative experience. Additionally, in almost every case, the group of users who had negative experiences on platforms were also more lonely than the national average of loneliness. That said, the number of users of some of these platforms who report having a negative experience is small, so these data should be interpreted with caution. We will revisit this question in a future survey with a larger sample to determine the reliability of these estimates.

If we look at the rates of users reporting negative personal experiences based on whether they are lonely or not in the graph below, we do see a general pattern where lonely people are more likely to report having a negative experience on social platforms than non-lonely people are. Again, given the correlational nature of these data, we cannot determine whether these negative experiences increase loneliness, loneliness increases people’s tendency to report and/or go places where they may have more negative experiences, or if there are extraneous variables that actually create the appearance of a relationship between loneliness and negative experiences. That said, historical research does demonstrate that negative experiences similar to those that may now be found on social media, like bullying, harassment, and social exclusion can increase loneliness.

Beliefs About Social Media and Loneliness

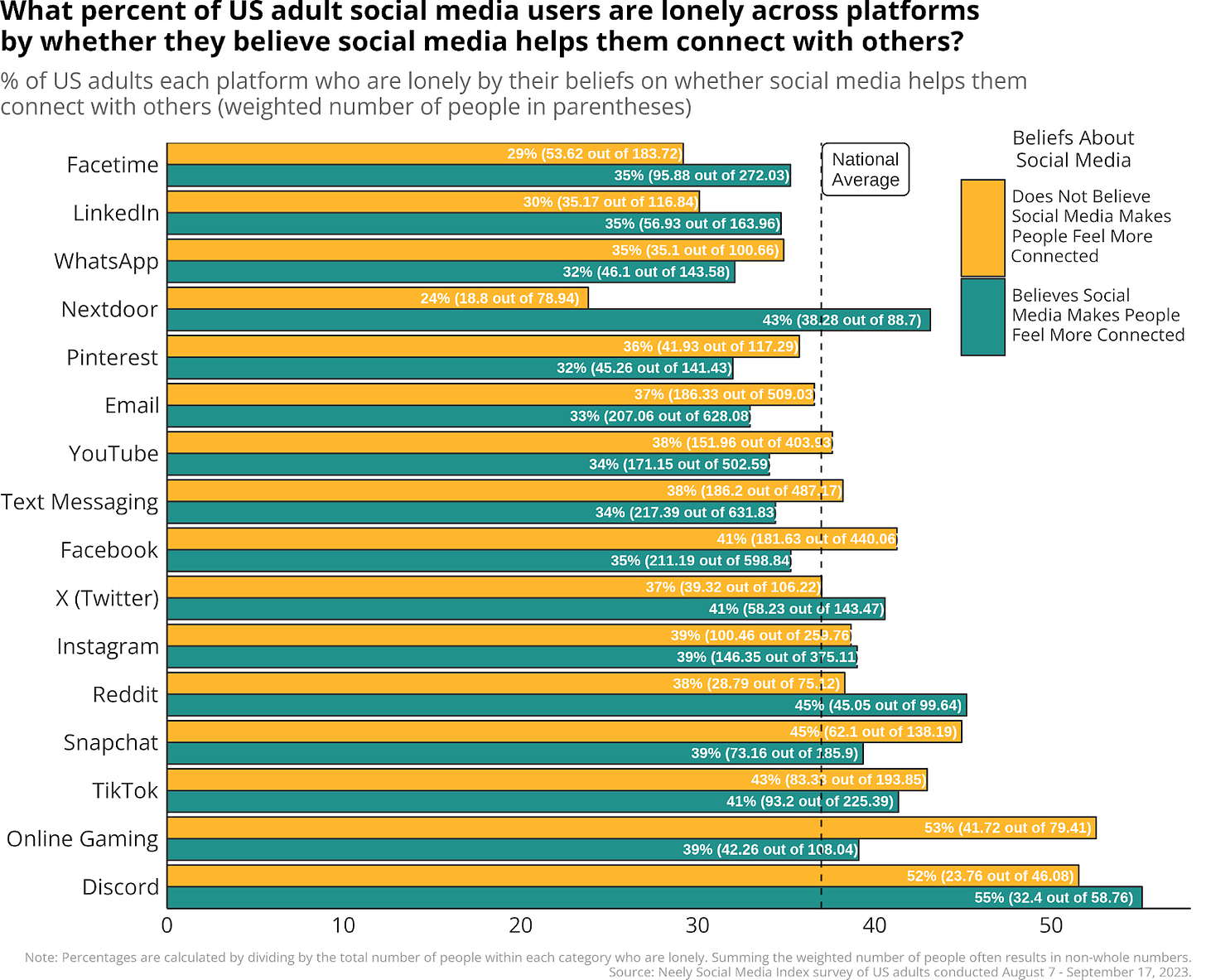

Some research also suggests that people’s beliefs and motivations for using social media may also moderate their experience. If so, and if people’s experiences on social media, then loneliness may differ by whether the users believe that social media helps them connect more to other people vs. do not help them connect with other people.

Earlier in this report, we described a short questionnaire that assesses people’s beliefs that social media helps (or does not help) them connect more with people. In the graph below, I compare loneliness among users of different social platforms who do vs. do not believe that social media helps them connect more with people. Across 9 of the 16 platforms, we see that users who believe social media helps them connect with other people are less lonely than users who do not believe that social media helps them connect with other people. The only 2 platforms where users who believed social media helps them connect more with other people were lonelier than their counterparts were Facetime and Nextdoor. Facetime is a direct communication-oriented platform, which is a subtype of platform with elevated rates of meaningful connections with others, and Facetime’s user base tends to be wealthier, which also corresponds with lower levels of loneliness. Why the pattern is the reverse for Nextdoor is less clear.

Conclusion

In 2023, the US Surgeon General declared a loneliness epidemic in America, calling it a serious public health crisis. To what extent are changes in our social technology implicated in this crisis - and to what extent should we call it a crisis? Our review of the data suggests that, while it is true (and concerning) that loneliness substantially increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, loneliness has also been decreasing in prior decades. Additionally, at least one recent survey suggests that loneliness has declined to its pre-pandemic levels. That said, it’s unclear what prevalence should constitute an epidemic. Loneliness is certainly harmful and it’s better when fewer people are lonely, but does 30% of people being lonely constitute an epidemic? That is beyond the scope of our expertise and data, but it is an important experience.

More relevant to the current investigation, could the loneliness that people are experiencing in the modern age be uniquely related to technology designed, in part, to help people connect?

Based on the data we have now collected, we think there is a relationship between social media, loneliness, and connection, but it is not a straight-forward one. Overall, we find that the number of different social media and communication platforms people use corresponds with slightly greater loneliness, but the relationship is small. Self-reported frequency of social media use does not correlate with loneliness, which could be due to the two variables being unrelated, or something else, like people being unable to accurately self-report how frequently they use social media or effects that go in different directions canceling out. Users of social platforms that are more oriented towards direct communication tend to be less lonely than users of the more traditional social media platforms. One possibility for this association could be that people who use direct messaging platforms may be more social individuals; another possibility is that traditional social media platforms may be more likely to trigger people’s fear of missing out (FOMO) than other social platforms, and FOMO is associated with greater loneliness. Of course, other possibilities exist as well. We conclude that, overall, social media use and loneliness are somewhat related, but that relationship is complex and not easily understood using correlational data.

Such complexity highlights the need for running experiments. Social media companies could test interventions to promote more meaningful connections between users, perhaps by surfacing healthier conversations or recommending welcoming groups to users, which might reduce loneliness. In the current correlational data, users reporting more meaningful connections generally were less lonely than those reporting fewer meaningful connections on these platforms. Similarly, companies could also take more action in combating negative user experiences, like bullying, harassment, and toxicity that is so commonly found online, which might also reduce loneliness. In the current data, users reporting more negative experiences were more lonely than those reporting fewer negative experiences. Without these companies running experiments to test these hypotheses, we cannot determine whether these experiences directly affect loneliness.

We think companies should be incentivized to run such experiments for at least three reasons. First, even if product changes do not directly affect users’ loneliness, companies still stand to benefit as more positive user experiences and fewer negative user experiences can improve companies’ financial bottom lines. Second, there are broader gains to society when people feel less lonely and more connected. Finally, science stands to benefit as well. The psychology of how and why people connect more or less effectively is fascinating, and running experiments with social technology can explicate previously unknown aspects of the psychology of connection - such as when people are undersocial, why and how they feel understood in conversation, and when people are likely to show kindness toward others.

We hope technologists and researchers alike will take advantage of new opportunities to use social technology to reduce loneliness and contribute to the science of connection.